Note:

MRV EFFECTIVENESS GUIDE

Please Read Before Providing Comments

Thank you for taking the time to review this new guidance document and to share your feedback.

INSTRUCTIONS

If you are a new user on ScribeHub and you want to provide comments – click on the new comment button located on the right side.

You will be asked to register by clicking on the yellow register button.

If you are already registered on ScribeHub, please sign in (top right corner) before accessing the document and commenting.

REGISTERING

If you are not already registered to ScribeHub, you will be asked to register on the platform - providing your email address, name and creating a password. You will then be sent a confirmation email. Click on the Confirm my account link in the email and you will be redirected to the login screen for ScribeHub. Enter you email and password and you will then have access to the document.

Please note that your name and email address will be used by NovaSphere to record the list of people providing comments during this public consultation. Remember the email and password you use to register as this information will always be required to log in to ScribeHub.

COMMENTING

Once on ScribeHub, please use the comment button beside each section header to input your feedback.

Pressing on the + sign will open a dialog box where you can input the title of your comment, the related section of the document, and your comment. You can also attach documents to your comment and assign a label (e.g. editorial comment, technical comment, etc.). Keep in mind that comments are publicly visible (similar to posting a comment on LinkedIn). You can also reply directly to a comment already posted.

The guidance document will be proofread before publication, so there is no need to flag minor editing issues.

TIMELINE

Please provide your feedback by June 1, 2022.

CONTACT

If you encounter any problems at using ScribeHub or questions about this public consultation, please email tom@novasphere.ca.

THANK YOU!

Guidance to Assess Effectiveness of Climate MRV Systems and to Develop an MRV Strategy to Enhance Effectiveness

Version 1, March 2022

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

DISCLAIMER

The information presented in this publication is intended to provide guidance to experienced MRV practitioners in the preparation of Climate MRV (measurement, reporting, verification) strategies and systems. It remains the sole responsibility of practitioners that all work performed conforms to applicable legislation, regulation and standards. This publication is not a substitute for prudent professional practice and due diligence. References to external organizations, agencies, websites and publications, and the provision of downloadable reference materials, do not constitute an endorsement of any of these sources of information. While care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information presented herein, this publication is intended solely as a document of guidance intent. The authors, contributors and sponsors assume no responsibility for consequential loss, errors or omissions resulting from the information contained herein. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of contributors and sponsors.

USING THIS DOCUMENT

This document has been developed in support of collaboration by the Government of Canada (Environment and Climate Change Canada, ECCC) and partner countries in the Pacific Alliance and West Africa on MRV Innovations. This document acknowledges activities to advance Climate MRV Governance are ongoing, and that such activities are related to efforts to advance Climate MRV Systems. The intended user of this document is anyone that is, or will be, planning, developing, implementing or building capacity for a Climate MRV System, and/or those users responsible for enhancing the effectiveness of such Climate MRV System. This document can also be helpful to anyone interested in related efforts to advance Climate MRV Governance

This document provides general guidance (e.g., core concepts and framework, key terms and figures) to explain “Effective Climate MRV”. The guidance is accompanied by tools (e.g., step-by-step process, templates) that practitioners can use to assess the effectiveness of an MRV System and subsequently develop an MRV Strategy to enhance the effectiveness of the MRV System. work is ongoing to develop additional guidance to support the application to the MRV categories of inventories, mitigation, finance and NDCs.

This document uses a combination of boxes and colouring to emphasize key points of information, references and examples intended to aid learning and reading:

- Green boxes for terms and definitions

- Blue boxes for examples from stakeholder findings/experience

- Orange box for explanatory examples of key points

- Bolded text to emphasize key points within the body of text

INTRODUCTION

Building capacity to enable transparency of climate actions is fundamental to the global effort to address the climate crisis1,2, for example to help de-risk and accelerate feasible mitigation actions. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change3 (UNFCCC) emphasizes the importance of structured approaches to climate-related Measurement, Reporting and Verification (hereafter “Climate MRV”). Climate MRV can enhance transparency and accountability through assessment of:

- progress against objectives and targets;

- continuity, coordination and impact of mitigation actions; and

- use of finance, technology and capacity-building climate outcomes.

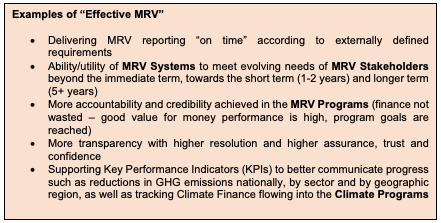

Climate MRV can be applied to various sectors and types of climate actions. For example: mitigation actions, climate finance, and greenhouse gas (GHG) and short-lived climate pollutants (SLCP) inventories. What constitutes “effective” Climate MRV (refer to Figure 1) will vary by:

- scale of the climate action – national, regional, program, organization, facility, technology, product, project;

- the intended uses – regulation, investment, markets;

- stakeholders – government, financiers, consumers;

- and MRV Outputs of the MRV System – reports, data, units.

A key consideration for the design and implementation of an MRV System is its effectiveness: ensuring the MRV System is successful in achieving MRV Stakeholders needs and goals. For Climate MRV practitioners, understanding what constitutes effective (and the optimal level of effectiveness) is a core design challenge of an MRV System.

This document assists climate practitioners responsible for developing and implementing an MRV System with guidance on how to optimize its effectiveness.

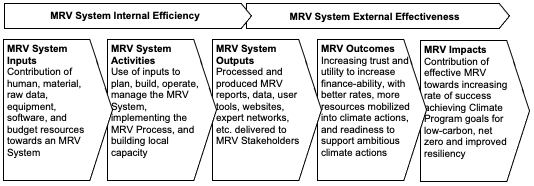

This document describes a conceptual framework of MRV Effectiveness for an MRV System, and applies a Theory of Change perspective (e.g., inputs > activities > outputs > outcomes > impacts) to it. The MRV System is ‘Effective’ in the context of MRV Stakeholder needs and goals (refer to Figure 1).

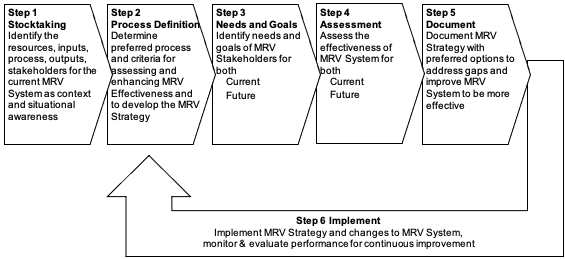

This document provides practical guidance and tools for users to assess the effectiveness of their MRV System and to develop an MRV Strategy to enhance effectiveness, using the following stepwise process (refer to Figure 1):

identify the components and activities, and overall situational context, for the current MRV System

determine the preferred process for assessing and enhancing the effectiveness of the MRV System

identify current and future needs and goals of MRV Stakeholders for current and future MRV Systems

assess needs, goals, gaps, and options to determine effectiveness and design an MRV Strategy to enhance effectiveness of current and future MRV Systems

assemble the assessment and obtain support to develop an actionable MRV Strategy to increase the effectiveness of the MRV System

follow through and activate the MRV Strategy and changes to the MRV System, then monitor and evaluate the performance of the MRV System to enable continuous improvement

CONTEXT FOR CLIMATE MRV

Climate MRV is an indispensable part of implementing an effective climate change response, whether for a national Low Emissions Development Strategy (LEDS); sub-national stakeholders such as local communities; industry sectors; or individual companies or facilities reducing emissions and transforming to low-carbon and net-zero activities. The design, build and operation of an MRV System, to meet relevant stakeholder needs involves significant time and resources, as well as an appropriate MRV Strategy. The context around Climate MRV has developed over the last 30 years and it continues to evolve. At the core of Climate MRV is the MRV System, as illustrated in Figure 1.

There are two types of MRV Systems corresponding to different purposes. The first, referred to as a “micro-MRV System” or “entity-level MRV System”, is operated by an organization such as an industrial facility or an emission reduction project to monitor activity data (mainly from onsite activities), and verify the quantified and reported results as MRV Outputs. These are submitted to MRV Stakeholders such as MRV Programs managed by governments or voluntary initiatives.

The second type of MRV System, referred to as a “macro-MRV System” or “program-level MRV System”, is operated by an MRV Program that generally includes additional MRV-related activities such as compiling and reviewing MRV Outputs for each of the entities obligated to perform the micro-MRV. The macro-MRV System is established within Institutional Arrangements and supports one or more Climate Programs such as the national GHG inventory, mitigation and carbon offsets, cap and trade emission trading schemes, climate finance, capacity building, and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Further, the macro-MRV System is usually guided by an overarching Climate Governance framework – a fundamental prerequisite to successfully design and implement climate MRV Systems for relevant, effective and efficient climate action strategies.

An essential first step is to understand the specific context for the MRV and the parameters in which it will operate, for example:

- Who are the MRV Stakeholders and what are their needs and goals as objectives of MRV?

- What MRV Frameworks, MRV Principles, and MRV Standards guide the MRV Process (doing the MRV)?

- What sources and activities are Measured and Monitored? What data and information are Reported? What is Verified and to what level of assurance?

- What are the MRV Inputs (resources, data, expertise, tools, budget)?

- What management system(s) support the MRV System?

This section presents a brief description of the core concepts and context of the MRV System as the foundation for subsequent sections explaining MRV Effectiveness and providing guidance to assess MRV System, and to develop an MRV Strategy to enhance the MRV effectiveness of the MRV System.

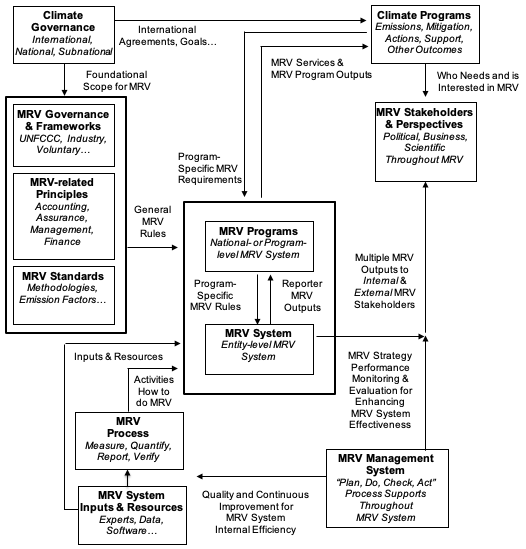

Figure 1: Overview of Climate MRV in context of Governance, Programs and Stakeholders

Climate Governance and Climate Programs

The primary purpose of Climate MRV is to provide MRV Stakeholders with information to support decision making (e.g., identify opportunities, track implementation, assess impacts, spend money, regulate industry, tax consumption), as well as provide assurance that there is transparency and accountability with such information. Climate MRV provides MRV Stakeholders with confidence to be able steer Climate Governance to advance the ambition of Climate Programs. Conversely, Climate Governance is also a fundamental building block to plan and implement functional MRV Systems.

Climate Governance encompasses:

- International Agreements and Initiatives (UNFCCC, Paris Agreement, Financial Stability Board, Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD));

- National Government Policies, Strategies, Laws and Regulations; and

- Subnational Government (provincial, state, regional, local) Policies, Strategies, Laws and Regulations.

Climate Governance agreements and organizations prescribe the high-level goals and directions that create the foundations for both MRV Governance and for Climate Programs.

Climate Programs encompass the GHG emissions, mitigation actions, support and other outcomes that are active or planned to be implemented, for example:

- GHG and Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCP) Emissions Inventories

- GHG Emissions Allowances and Cap & Trade Emissions Trading Schemes

- Mitigation Emission Reductions and Carbon Offsets

- Carbon Taxes and Credits

- Climate Technologies

- Climate Finance

- Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

MRV Governance and Frameworks

Climate Governance agreements and organizations prescribe foundations, including MRV Governance and Frameworks, MRV-related Principles, and MRV Standards that enable the overall governance of Climate MRV for accountability and assurance.

MRV Governance and MRV Frameworks are established by various organizations, including:

- UNFCCC MRV and the Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF)

- Standards Development Organizations (SDOs), such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO);

- Financial Sector (International Accounting Standards Board – IASB; International Federation of Accountants – IFAC; Financial Stability Board, Task Force on Climate-Related Disclosures – FSB-TCFD; International Sustainability Standards Board – ISSB)

- Voluntary Programs (NGOs; GHG Protocol)

- Industry Associations.

MRV Frameworks are high-level and do not prescribe detailed requirements for specific climate actions. Therefore, MRV Principles are established, often within MRV Standards, to provide direction and guidance so reported information represents a faithful, true and fair account, and can be relied upon by decision makers. Examples of MRV Principles include:

- GHG Accounting Principles (TRACC: Transparency, Relevance, Accuracy, Consistency and Completeness)

- GHG Verification Principles

- Management Principles

- MRV Program Principles

- Climate Finance Principles

- MRV Effectiveness Principles

MRV Standards is a term encompassing standards (e.g., ISO), guidelines (e.g., IPCC), protocols (e.g., GHG Protocol), methodologies (e.g., CDM), as well as specifying emission factors and other requirements. Well over 1000 MRV Standards have been developed for different categories and levels of application of MRV.

Categories and Levels of Application of MRV

MRV is commonly applied to the following categories:

- MRV of emissions: estimation and tracking of GHG and SLCP emissions over time at national, regional, sector, project or facility levels;

- MRV of actions: assessing impacts of mitigation policies and actions, at the project, facility, sector or national scales;

- MRV of support: encompasses international and intranational finance flows, technology transfer, capacity building and their impacts.

- MRV of other outcomes: connecting GHG mitigation actions with co-benefits such as energy access, adaptation or SDGs.

These applications overlap and should be harmonized. For example, MRV can track financial support for implementing a new technology in a sector, the emissions reduced and avoided compared to business as usual (BaU) within the sector, the change in absolute emissions in the sector over time, and the number of jobs created as a result. Much of the raw data (such as number/scale of technology deployment) will be inputs for each MRV category, while other aspects (such as change in employment) will require separate data monitoring.

MRV Stakeholders

MRV Stakeholders are diverse with different roles, objectives and perspectives. The main groups of MRV Stakeholders include:

- Climate Policy Makers and Climate Programs, such as national or subnational governments, private sector and voluntary programmes, managing regulations or incentive schemes to facilitate emissions reductions

- Reporting Entities and Project Developers, such as large corporates, facilities, installations, and SMEs (small- and medium- sized enterprises)

- MRV Programs and MRV System Operators, including the government bodies, which are the ‘hands-on’ experts and managers that also connect the flow of MRV information among Stakeholders

- MRV Service Providers such as consultants, trainers and auditors/verifiers, as well as those that develop MRV solutions such as tools and software for GHG accounting, modeling, communications

- MRV Standards and Accreditation Organizations, such as international, national, and sector-level multi-stakeholder initiatives

- Financial and Market Actors mobilizing private and public climate finance, such as financial institutions, commercial banks, development banks, insurers, climate funds, emission trading markets

- Public and Civil Society (Non-Governmental Organizations), such as research and academia, associations, cooperatives or unions

MRV Stakeholders need different MRV information that can vary in fundamental ways, for example:

- Type and level of detail of information (government reporting templates, public report)

- Time frequency (annual, monthly, daily, hourly)

- Level of Assurance (market grade or compliance grade verification, or company brand goodwill confidence and limited transparency)

Furthermore, MRV Stakeholders have different perspectives, or lenses, about the MRV information that can be characterized as:

- Scientific (natural or chemical process understood; quality controls for accuracy)

- Business (costs and benefits; economic efficiency and economic gains)

- Political (fit for purpose; accountability, fairness; human/physical capacity).

MRV Stakeholders have needs (e.g., a minimum viable product (MVP) of an MRV System for reliable timely and quality mandatory reporting) and goals (e.g., increase climate finance for higher ambition NDCs) that an MRV System is expected to help satisfy.

MRV Programs

MRV Programs directly support, and are sometimes part of, Climate Programs. MRV Programs are part of the Institutional Arrangements4 of the government bodies (i.e., legal mandate and operational authority) as well as voluntary programs, and can include operation of a macro-MRV System5 (see below).

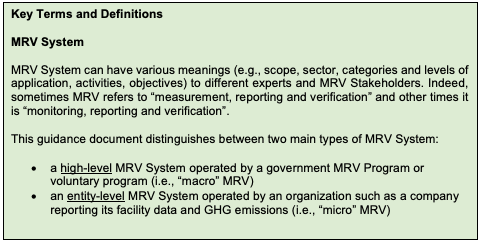

MRV Systems

There are different types of MRV Systems, therefore it is important to be clear about the differences (e.g., scope, sector, categories and levels of application, activities, objectives) for MRV Stakeholders6. Indeed, sometimes MRV refers to “measurement, reporting and verification” and other times it is “monitoring, reporting and verification”.

This guidance document distinguishes between two main types of MRV Systems:

- macro-MRV System – which is a high-level (e.g., national, regional, international), operated by a government MRV Program7 or voluntary program with a mandate to produce MRV Outputs on behalf of MRV Stakeholders. A macro-MRV System typically receives, assesses and compiles MRV Outputs from entity-level MRV Systems.

- micro-MRV System – which is at the entity-level (e.g., company or facility or project), operated by an organization8 reporting data and GHG emissions to MRV Stakeholders (e.g., MRV Program).

MRV Inputs and Resources

An MRV System uses various resources and has many inputs (refer to Figure 1) that vary depending on the category or level of application of MRV. Examples of inputs and resources to the MRV System include:

- Human capacity operating and managing the MRV System

- Physical capacity such as measurement devices (meters, sensors, scales, satellites, offices, vehicles)

- Data and Information such as raw activity data (e.g., m2, ha, m3, litres, tonnes, kWh, population), metadata (e.g., time, location, owner, conditions), qualitative data, data series (e.g., historical, current, projected)

- Standards such as IPCC Guidance, CDM Methodologies, GHG Protocol, industry standards

- Tools such as GHG reporting software, data and information management system software, emission factor databases

- Budget provided by an MRV Program or by others such as donors, corporate management of the reporting entity.

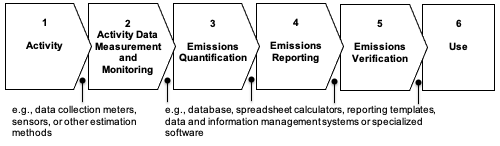

MRV Process

The MRV Process varies for different types of climate actions, for example GHG emissions inventories and mitigation emission reduction projects. However, most MRV follows a process as depicted in the following figure, with description below.

Figure 2: MRV Process

Box 1: Activities cause direct GHG emissions (e.g., industrial process emissions) or indirect GHG emissions (e.g., purchases of electricity generated from the combustion of fossil fuels emits carbon dioxide). Meters, sensors or estimation methods measure and monitor activities and GHG emissions.

Box 2: Measurement and monitoring of activities causing GHG emissions to create and collect “activity data” that are stored in a database or other data storage and then transmitted for GHG emissions quantification (e.g., automated electronic data transfer, emailed spreadsheet, or paper-based systems).

Box 3: Quantification of GHG emissions by applying GHG emissions factors and methodologies to the measured and monitored activity using spreadsheets or other specialized software. Analysis of the results and preparation for reporting (e.g., annotate the “data trail” for transparency and review).

Box 4: Reporting of quantified GHG emissions and related information, including additional analysis and contextualization of the results for communication to specific MRV Stakeholders (e.g., reports to government authorities, company annual reports, online databases). Preparing data and information to be available to verifiers (e.g., sending information or providing controlled-access via an online portal).

Box 5: Verification to determine GHG emissions and related information has been measured, quantified and reported to a certain level of assurance. Verification is communicated to users typically as a verification report and/or verification statement.

Box 6: Final use of GHG data and information, such as for national inventories, facility-level emissions registry, project-level emission reduction mitigation registry, climate finance, or public communications.

MRV Outputs

An MRV System, via MRV Inputs and the MRV Process, produces various direct and indirect MRV Outputs for MRV Stakeholders (refer to Figure 1) that vary depending on the category or level of application of MRV, as well from micro-MRV Systems or macro-MRV Systems. Examples of outputs from the include:

- micro-MRV Systems produce mainly specific documents such as MRV reports, for example an annual GHG inventory, GHG mitigation outcomes emission reduction report, GHG verification report, including supporting information and data (whether verified or not)

- macro-MRV Systems produce synthesis reports for MRV Programs such as performance metrics about the timeliness and completeness of MRV reports received for a period of time, as well as supporting resources such as best practice case studies, knowledge hubs and expert networks

MRV Management System

Organizations and programs implement various types of management systems to enable quality control and continuous improvement to achieve goals. Management systems include policies and procedures to assess, maintain and advance performance (e.g., quality, efficiency, effectiveness).

There are many types of management systems, for example:

- Data management systems9,10

- Information management systems11

- Knowledge management systems12

- Change management systems13

- Project management systems14

- Quality management systems15

- Environmental management systems16,17

- GHG emissions management systems18

A management system integrated with the MRV System can include data and information management systems for quality and continuous improvement (e.g., increase data timeliness and accuracy). Furthermore, the management system approach can be applied to other aspects of the MRV System (e.g., MRV Inputs and resources, the MRV Process, MRV Outputs). Indeed, an MRV Management System can support both internal efficiency of the MRV System (i.e., “value for money” of MRV Outputs delivered for MRV Inputs provided) as well as external effectiveness (i.e., how the MRV System supports Climate Programs to achieve climate goals)19.

An MRV Management System can include elements of the different management systems listed above. Change management (guided by an MRV Strategy) is an important part of the Theory of Change to enhance MRV Effectiveness of Outcomes and Impacts attributed to the MRV System.

It is essential to understand the core concepts of an MRV System described above to develop a clear understanding of what is meant by “Effective MRV”, which is described in the next section.

EXPLANATION OF MRV EFFECTIVENESS

The primary objectives of Climate MRV are to obtain and assess credible information about climate actions and to assess if performance targets are being achieved. But MRV Systems can be more than a passive ex post accounting process. This guidance document sets out how “effective MRV Systems” can add real value to MRV Stakeholders. For example, in contributing towards (being more effective in) building trust between partners, attracting and unlocking access to more climate finance, and gaining other support to empower MRV Stakeholders to achieve climate goals.

Moving beyond traditional MRV Systems that provides high-level GHG information with limited insights, towards high-resolution and high-confidence information (e.g., historic, current, projected data) helps mobilize and monitor much larger amounts of private finance climate investments necessary to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement and build sovereign, national MRV Systems.

An MRV System is not effective if it:

- is not able to report on time to an MRV Program or government authority;

- does not provide a complete set of information;

- has unknown accuracy;

- does not provide consistently recorded and transparently reported information to enable verification.

Such an ineffective MRV System cannot readily assess the outcomes and impacts (e.g., emission reductions) from implementing climate actions. Therefore, much effort can be wasted in attempting to discern the level of success in achieving climate goals. This dissuades investment in implementing climate actions and slows progress toward achieving climate goals.

MRV Stakeholders define what is “effective” for them. MRV Stakeholders might have different needs (e.g., a minimum viable product (MVP) of an MRV System to increase the level of accuracy of measurement and frequency of monitoring to enable reliable timely and quality mandatory reporting) and goals (e.g., increase climate finance for higher ambition NDCs) – so the determination of “effectiveness” might vary among MRV Stakeholders. The MRV System operator must ensure the MRV Process and MRV Management System is able to meet the variety of needs to be considered effective.

In practice, establishing an MRV System that satisfies multiple MRV Stakeholders’ needs and goals is simplified by identifying shared needs and goals, and several requirements externally defined by MRV Governance and Frameworks or Climate Programs. For example, through the IPCC or Paris Agreement.

The categories and levels of application of MRV will have different criteria to determine “effectiveness”, which is described in latter sections for NDCs, inventory, mitigation and finance. Emissions may be regulated and thus require accurate measurement and timely reporting. Certain types of climate actions may generate transactable assets such as carbon credits20, which require a high Level of Assurance (LoA) in Verification. In contrast, more narrative and qualitative assessment processes may be appropriate for some climate actions (e.g., inform and support consumer preferences and behaviour for a low-carbon lifestyle).

MRV Systems evolve and improve over time. It is common to have a simple and limited scope MRV System initially, while allowing for continuous improvement. As an MRV System matures, its effectiveness may change over time in relation to the changing needs and goals of MRV Stakeholders.

Most MRV Governance and Frameworks provide guidance on what can or should be done beyond minimum requirements. For example, the IPCC Guidelines21 discuss increasing accuracy and relevance of data (Tier 1, 2 and 3), and that national inventories should include a goal to improve accuracy and coverage over time. The main MRV Stakeholder for national inventory reporting to the UNFCCC is the national government, who might seek to move to higher accuracy data (e.g., from Tier 1 to Tier 2) in key sectors to demonstrate improvement and facilitate better understanding of the impacts from a range of interventions. An MRV System that has, and that utilizes, the ability to achieve higher accuracy is considered “effective”.

Large organizations that include multi-stakeholder and multi-year initiatives often formalize methodologies and systems to support better management, including MRV. For example, the “Theory of Change”22,23 methodology is used to support planning and implementation of measures and interventions by the UN to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals24, including Climate Action (SDG 13). MRV (and the related Monitoring & Evaluation25,26 (M&E)) assesses the performance of outcomes and impacts of interventions (e.g., NDCs, support, climate finance, mitigation, inventories). The Theory of Change methodology is flexible, often it is applied with a focus on a primary priority such as climate action, but it can also be applied with a focus on any point in the value chain such as MRV.

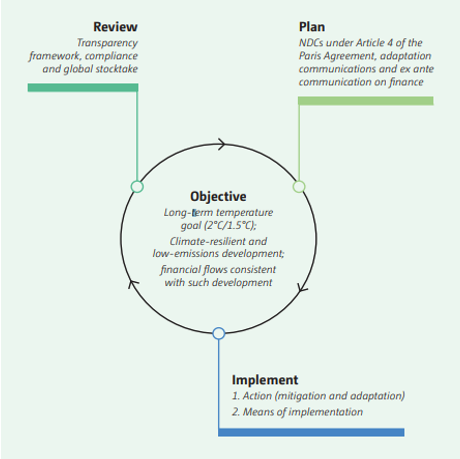

Figure 3: Example of continuous improvement in MRV Systems: Nationally Determined Contributions and the Enhanced Transparency Framework in the overall cycle of ambition under the Paris Agreement27.

Figure 4: Theory of Change perspective for internal efficiency and external effectiveness of an MRV System

MRV System effectiveness is not a Boolean state of “effective or not effective”, but a continuous scale with increasing value and utility to MRV Stakeholders as effectiveness increases. There will be some minimal functional point (e.g., a Minimum Viable Product) below which the minimum needs of MRV Stakeholders (which change over time) are not satisfied. This is discussed further in the following section.

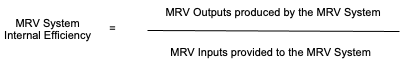

MRV System internal efficiency assesses the MRV Outputs produced relative to the MRV Inputs provided. MRV Inputs to the MRV System may be provided by an MRV Program or others (e.g., donors, corporate management of the reporting entity).

For example, in year 1 an MRV Program budget resulted in 3 reports. MRV System internal efficiency improved during year 2, resulting in 4 reports for the same (or less) budget. MRV System internal efficiency is improved by overcoming shortcomings, for example:

- wasted time and effort (experts get better over time, are faster and use the correct data)

- poor coordination (contributors become more familiar with expectations and processes)

- wasted budget (key priorities addressed with appropriate solutions and experts)

- process failure (formalizing procedures and responsibilities among team members)

- lack of institutional arrangements relating to the MRV process are clarified and formalised

- deficient technical, institutional and systemic capacities are improved or resolved.

In this example, the MRV System internal efficiency improves by 33% (if inputs remain the same).

MRV System external effectiveness assesses the MRV Outcomes and MRV Impacts relative to MRV Stakeholders’, such as Climate Programs (e.g., policies, strategies, NDCs), needs and goals. For example:

- attracting and accelerating more climate finance (e.g., private businesses increase investment by 50% per year)

- obtaining better financing terms (e.g., lower interest rates, grace periods)

- agreeing preferential trade terms

- achieving mitigation targets.

MRV System external effectiveness can be enhanced by implementing an MRV Strategy (see next section) to help identify and address MRV Stakeholder needs and goals.

Using the example above, if the 4 reports produced by the enhanced MRV System mean more timely information available to decision makers (e.g., quarterly reports), an investment fund has greater confidence in the ability to monitor progress, and thus can increase investment. For this MRV Stakeholder, the “need” is timely information. The MRV System improves internal efficiency and external effectiveness. Thus, the MRV System has increased effectiveness.

Conversely, if the 4 reports produced by the enhanced MRV System are more timely but do not improve accuracy or transparency, the investment fund might not have sufficient information to manage investment risk, and cannot increase investment. For this MRV Stakeholder, the “need” is accurate and transparent information. The MRV System improves internal efficiency on timeliness, but not external effectiveness. Thus, the MRV System has not increased effectiveness.

In summary, effective MRV Systems are optimised to increase utility and efficacy for MRV Stakeholders. An MRV System creates value by de-risking and supporting cost-effective and scalable climate actions. Such an MRV System can be more user-friendly, cheaper to operate and maintain within a “continuous improvement” MRV management system; and be faster and easier to expand to support evolving climate actions, and MRV Stakeholder needs and goals.

GUIDANCE TO ASSESS AND ENHANCE MRV SYSTEM EFFECTIVENESS

This section provides guidance to develop a practical MRV Strategy to enhance effectiveness. For new users, awareness and capacity building, as well as learning-by-doing are important objectives.

Establishing and following an appropriately defined and structured process supports the development of a credible MRV Strategy. A credible MRV Strategy includes an actionable plan that has a better chance of being appropriately resourced and successfully implemented. In turn, this builds an MRV System that is effective for MRV Stakeholders and compatible with national and international partners. This enables knowledge exchange and coordination among countries to further optimize the MRV Systems (e.g., reduce duplication or inconsistencies) and facilitate climate actions towards shared climate goals.

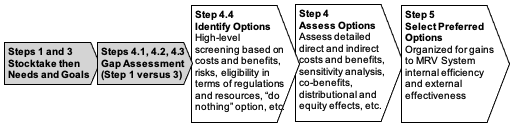

Figure 5: Process for developing an MRV Strategy to assess and enhance MRV System Effectiveness

Figure 5 depicts a step-by-step and iterative process. In practice, the process is more continual and dynamic, and should be performed considering the interconnectedness of the steps. For example, when assessing the current MRV System (Step 1) the user may also be aware of MRV Stakeholders needs (Step 3) and foresee gaps that will be part of the gap assessment (Step 2). Hence, while this guidance document depicts the process in a step-by-step approach to be easier to understand, in practice the process is inherently interconnected.

identify the parts of their current MRV System (e.g., policy, frameworks, institutional arrangements and programs, components such as data, standards, resources) and the activities involved in their current MRV System (e.g., using resources and inputs to perform the MRV Process from plans and collecting data to internal reviews and delivering outputs such as reports) to determine the overall situational context

determine the preferred process and criteria as the basis for the work (e.g., an initial effort with limited scope and resources such as an “80-20 rule” intended to achieve incremental change and quick wins for the MRV System, or a high ambition with substantial resources available to achieve transformational change of the MRV System) to assess and enhance the effectiveness of the MRV System

identify the current and future needs and goals of MRV Stakeholders (e.g., national strategies, UNFCCC reporting, climate finance and markets) for the current and future MRV Systems

assess needs, goals, gaps, and options to determine effectiveness and design an MRV Strategy to enhance effectiveness of current and future MRV systems (e.g., utilize a gap analysis and an options analysis)

assemble the assessment (e.g., preferred options to address the gaps) and obtain support to develop an actionable MRV Strategy to increase the effectiveness of the MRV System to satisfy the needs and goals of MRV Stakeholders

follow through and activate the MRV Strategy and changes to the MRV System, then monitor and evaluate the performance of the MRV System to enable continuous improvement

An appropriately defined and structured process, pragmatically implemented, to develop a credible MRV Strategy to assess and enhance the effectiveness of an MRV System has a higher chance of success than an ad hoc process.

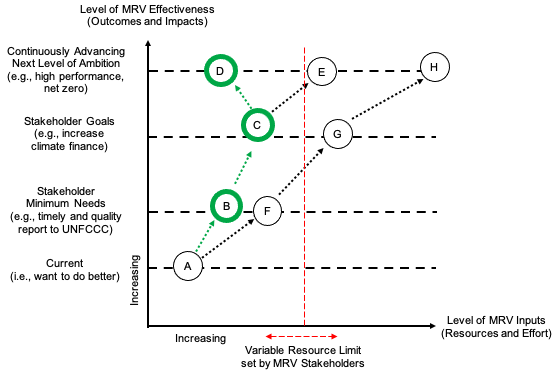

Figure 6 illustrates how different approaches to an MRV Strategy can optimise the pathway to an effective MRV System according to the expanding needs (e.g., a minimum viable product (MVP) of an MRV System for reliable timely and quality mandatory reporting) and goals (e.g., increase climate finance for higher ambition NDCs) of MRV Stakeholders.

The following text describes:

- the levels/metrics of the:

- vertical axis for MRV Outputs and Impacts corresponding to MRV Effectiveness for MRV Stakeholders

- horizontal axis for MRV Inputs corresponding to resources set by MRV Stakeholders

- different pathways for developing an MRV Strategy through a structured process or an ad hoc process

Figure 6: Pathways to an Effective MRV System

Point A: determined based on steps to

- identify MRV Inputs and MRV Process activities of the MRV System (Step 1)

- identify MRV Stakeholders’ current needs and goals (Step 3)

- assess current MRV System relative to MRV Stakeholders’ current needs and goals (Step 4)

Point B via Arrow A to B: determined based on steps to

- identify MRV Stakeholders’ future needs and goals (at least minimum needs, e.g., quality and timely reporting to UNFCCC) (Step 3 continued)

- assess current MRV System relative to MRV Stakeholders’ future needs and goals (Step 4 continued)

- identify and analyze gaps between current MRV System and MRV Stakeholders’ future needs and goals; prioritize gaps to be addressed (Step 4 continued)

- identify and analyze options to address the gaps; prioritize appropriate options (Step 4 continued)

- develop initial cost-effective MRV Strategy with available budget and additional resources (Step 5)

Point C via Arrow B to C: determined based on steps to

- repeat the process to identify MRV Stakeholders’ next level of needs and goals (e.g., more ambitious to attract more climate finance) (Step 3 repeated, with more detail)

- assess MRV System (now at Point B) relative to MRV Stakeholders’ next level of needs and goals (Step 4 repeated, with more detail)

- improve initial MRV Strategy using a Change Management Process and MRV Management System for continuous improvement to meet MRV Stakeholders’ goals with the optimal balance of cost-effectiveness and readiness for longer-term MRV Stakeholders’ ambitions (Step 5 repeated, with more detail, and Step 6)

Point D via Arrow C to D: determined based on steps to

- repeat the process to identify MRV Stakeholders’ next level of needs and goals (e.g., high performance net zero climate solutions, maximize benefits) (Step 3 repeated, with more detail)

- assess MRV System (now at Point C) relative to MRV Stakeholders’ next level of needs and goals (Step 3 repeated, with more detail)

- improve further the MRV Strategy using cost-saving solutions (e.g., digital MRV technologies; stakeholder participation, including citizens, with open data platforms that engage and reward stakeholders as data providers and users to reduce MRV costs and to improve the utility of MRV data) (Step 5 repeated, with more detail, and Step 6)

In contrast, Points F, G, H represent an unstructured ad hoc process without an MRV Strategy. The ad hoc process, moving further to the right of the horizontal axis indicates an inefficient process. It might yet achieve an effective MRV System, but it uses more resources to achieve MRV effectiveness relative to a structured process with an MRV Strategy to achieve MRV Stakeholder needs and goals.

The above process (simplified for illustration) is applicable at various levels (e.g., national, sub-national, sector, GHG sources and sinks). The process can vary by level or from sector to sector depending on MRV Stakeholder priorities. For example, the MRV System for the energy sector meets MRV Stakeholders’ minimum needs such as a quality and timely report to the UNFCCC. At the same time, the MRV System for the land use sector might be more sophisticated and advanced to meet MRV Stakeholders’ goals of attracting high levels of climate finance for nature-based solutions.

In cases of sector or other delineations having different MRV Stakeholder needs and goals, the above process can be repeated for sub-sets of the MRV System as appropriate. The results from each sector or sub-set, based on the priorities of the relevant MRV Stakeholders, can be combined into an overall MRV Strategy that is cohesive, consistent and optimized for efficient use of limited resources, and is effective for MRV Stakeholder needs and goals.

Process to Assess and Enhance MRV Effectiveness

This section describes in more detail the six (6) step process illustrated in Figure 6.

Step 1 – Stocktake

Before developing an MRV Strategy, it is essential to identify the various elements of the current MRV System, and gather information about the context and situations in which the current MRV System operates. That is a “stocktake” to determine an initial “baseline” or starting point.

Referring to Figure 6, a stocktake should build an understanding of the relevant:

- external context including:

- Climate Governance and Climate Programs

- MRV Governance and Frameworks, and related MRV Principles and MRV Standards

- MRV Stakeholders, and their networks and interests

- internal context including:

- MRV Program in which the MRV System functions, including the MRV Rules and requirements

- MRV System itself, including resources, inputs, processes, activities and outputs, as well as MRV Management System

The stocktake provides the context and situational awareness needed to determine the process and criteria (see Step 2, next section) to guide development of the MRV Strategy. Typically a stocktake is undertaken by an individual or team with familiarity of one or more of the MRV elements illustrated in Figure 1. For example, the manager of an MRV System, or a government official overseeing an MRV Program or Climate Program. Stocktaking other elements is then often an ad hoc process of discovery.

The outreach for discovery and fact finding includes stakeholder engagement. This provides the opportunity to include an advocacy, awareness raising and capacity building function to the engagement process. MRV Stakeholders often consider MRV as a “pre-defined, fixed function” and do not usually appreciate the need and value of continuous improvement of MRV. Clear and concise communications on the need for, and benefits of, improving MRV System effectiveness in stakeholder engagement helps build broader support for resource allocation and helps overcome “resistance to change” when changes to the MRV System are implemented.

A more structured (i.e., less ad hoc) discovery process including structured surveys and templates will avoid bias, ensure completeness, and improve efficiency and results. A structured process should be appropriate to the context, timelines, resources and existing knowledge base. The steps below are a suggested approach that can be adapted as appropriate. The steps are presented sequentially, but in practice the steps can be performed individually or altogether simultaneously, for example, in identifying documents and making an initial assessment of their relevance and value.

A common technique to prepare for and inform situational context is a SWOT Analysis (i.e., Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats), which can be performed at a high level as illustrated in the following table.

| Positive | Negative | |

| Internal |

Strengths

|

Weaknesses

|

| External |

Opportunities

|

Threats

|

Step 1.1 – Preparation and planning

Although not all MRV Stakeholders and materials are known at the outset, “getting started” rarely starts from nothing. Previous documentation (e.g., consultant reports, organizational charts, funding applications), however high-level or dated, provide a basis to guide where to look and who to contact.

Preparation then includes:

- Identifying and assembling existing documentation and previous studies. These materials might be several years old, and might be out of date, with functions and responsibilities having changed or moved. These materials are an important resource however, as most stakeholders do not have a complete overview of MRV and might understand or label MRV elements differently. Typically, it is much easier to ask "Is this information still correct/current?” and “What has changed?" than it is to ask for a description of a current MRV System and context. Moreover, many elements, such as Climate Governance, will evolve and be updated, but remain housed in the same UN agency or government bodies for long periods.

- Collating references contained in existing documentation for follow up research.

- Identifying and collating contact information of MRV Stakeholders for stakeholder engagement, including where possible the contact coordinates titles and responsibilities of individuals working on the MRV System. Documents, or individuals undertaking the stocktake, might know the names of reports and their authors, and contact details of stakeholders. If not specific individuals, then institutions, such as the "Division of Climate Change, Ministry of Environment”.

- Developing or obtaining a draft schematic of the MRV System. This should, at a high-level, identify the inputs, activities, processes, outputs and flows of information.

- Developing an approximate relationship map of MRV Stakeholders. It may be helpful to provide an initial assessment of their relative importance to MRV, so that engagement time and resource allocation can be better planned and prioritized.

- Developing communications materials to inform stakeholders of the purpose of engagement, including (where relevant) the opportunity to include advocacy and capacity building aspects to these materials.

- Developing questionnaires / survey templates to collect the information, whether from documents or interviews.

- Planning and prioritizing stakeholder engagement, allowing time for parallel desktop/document research.

A simple way to facilitate the activities for Step 1.1 is to develop an initial version of Figure 1 to map MRV Stakeholders, relationships and to identify key resources or processes.

Step 1.2 – Fact finding and stakeholder engagement

Fact finding involves research and document review (including online research), and also engagement with MRV Stakeholders. These activities are mutually reinforcing, for example, reviewing an MRV Program document will inform discussions with an MRV Program manager, whilst saving time and focusing on resolving unknowns and understanding relationships. Conversely, discussions with MRV Stakeholders often uncovers additional resources (or provides updated/revised versions) such as websites and documents, the hierarchy between documents, and insights into organizational relationships.

Planning should have sufficient flexibility to allow for additional, previously unidentified relevant MRV Stakeholders to be included and engaged, as well as extra time allowed for additional documents/websites or processes to be assessed.

Stakeholder engagement should be planned and performed based on local needs and conditions. Very often a stocktake is undertaken by, or on behalf of the “owner” that is responsible for the MRV System, such as a national GHG emissions inventory group within a government department. Typically, they will facilitate and convene stakeholder engagement. It is good practice to manage expectations of MRV Stakeholders by setting out, in an initial contact or invitation to participate, the stocktaking and stakeholder engagement process. Typically, this includes:

- An initial workshop or webinar, sometimes called a “kick-off event” or “opening workshop” to which all identified MRV Stakeholders are invited, including:

- Welcome remarks or keynote presentation by a notable or senior official, such as a Minister or Head of Department;

- Overview presentation of the strategic objectives of the stocktake, linking the MRV System stocktake with MRV Stakeholder needs and goals such as UNFCCC reporting, attracting climate finance, or contributing to government development plans.

- Technical presentations providing more details and structuring the stakeholder engagement discussions to elucidate the processes, relationships, responsibilities and challenges of implementation of MRV, including identifying areas where improvements in MRV Effectiveness might be possible.

- Opportunity for questions and answers, and potentially “break-out group” discussions.

- Typically, an initial workshop is a half-day event. Where practical, the workshop should include a lunch or reception event, to enable human-to-human relationship building, as well as to uncover more informal assessments of challenges that are sometimes not fully stated in a more public setting.

A series of bilateral meetings should be organized following the initial workshop. The bilateral meetings enable discussion and information exchange in more detail, including identifying problems, solutions and areas for further development.

A closing workshop or webinar is typically conducted, in a similar format to the initial workshop, to summarize findings and recommendations proposed to guide future work for the key elements of the MRV Strategy.

The stakeholder engagement process does not have a minimum or maximum time but should be undertaken in a relatively compressed time to facilitate continuity of active engagement and to avoid “meeting fatigue”. The stakeholder engagement process should be less than 6 months, and ideally lasts 1-3 months.

The research phase and assessing documentation should include process, data and information flows, organizational structures and connections to MRV Stakeholders. Typically, some information might not be available or accessible, or it is incomplete, out-of-date, or there is more than one version addressing the same function. In such circumstances it is often necessary to make assumptions. It is important to clearly state any assumptions made and to include the rationale for why and how the assumptions are used.

The assessment of findings (Step 1.3) will be far more robust when the findings are well organized. Findings should be organized appropriately based the context, for example considering:

- What it is (reports, program guides, legislation, external studies, data)

- What type of MRV Output or product it is (GHG inventory report, GHG mitigation project reports, NAMA reports, sector studies, case studies, climate finance and other support)

- When it was it created

- Who created it, and contact information

- How it was created (consultative process, individual author, modified from external or international standards)

- When it was last used or modified

- Organizational and relationship mapping (groups, key members, governance maps of institutional arrangements or contractual arrangements, work flows).

It is important to document interactions with key persons, roles and responsibilities and their positions (divisions and teams) and hierarchies in each part of the organization(s) (organizational charts, flow charts).

The organization of research and fact findings should be reviewed with relevant MRV Stakeholders to ensure all relevant documents, functions and persons have been identified and included.

Step 1.3 – Assessment

Assessment should be performed on findings at two levels:

- corresponding to each component (document, data collection system, etc.)

- corresponding to each MRV category (for example, inventory reporting, which is made of a combination of documents, processes, data sourcing, and human involvement).

Although there might be redundancies and overlaps across the MRV System, this can be positive where it provides checks, calibration and back-up. It may also be negative, when it generates uncertainty or confusion, additional (unnecessary) workload, and/or competition between stakeholders. Redundancies should be clearly identified and assessed.

It is important for the assessment to be as objective as possible. This includes establishing at the outset if the information is “systemic” or ad hoc. This can be facilitated by asking the following questions on each finding:

- Is it current and up to date?

- Is it complete?

- Is it consistent with previous iterations, and comparable with good practice?

- is there an established process in place with regular flows of information? That is, is it currently operationally functional?

- Is there an identified role within the relevant organisation that is responsible for the process?

- Is there an individual in the role, who is sufficiently qualified and resourced to execute and maintain the process?

- Is it appropriate and relevant to MRV Stakeholders (for governments, industry, communities, finance, etc.)?

- How does each finding relate to the MRV Program:

- MRV Program Institutional Arrangements

- MRV Program Resources

- How does each finding relate to the MRV System and the MRV System users:

- MRV System Components (Data, methodologies, software, experts…)

- MRV Process and Users (projects, facilities, communities, finance…)

Step 2 – Determine the Process and Criteria

Users of this guidance can be working on MRV Systems that are at different starting points or “level of MRV maturity”. As well, users can have access to different resources to develop and implement an MRV Strategy. Therefore, this guidance outlines two processes corresponding to the appropriate levels of effort and rigour for, and priorities of, the user.

The Basic Approach is relatively faster and lower cost, appropriately geared to incremental changes and quick wins (the “low hanging fruit'').

The Advanced Approach is more detailed and rigorous with corresponding resource requirements, and so is geared towards deep transformational change to support ambitious goals.

It is common that users have some form of MRV System in place, whether old or new, or just relatively small. It is also common that the MRV System is neither well documented nor well understood. Therefore, this guidance document focuses on the Basic Approach because most users will be starting at that point.

However, the following table provides an example of how to characterize a user’s MRV System in terms of maturity levels to help the user decide between using a Basic Approach or Advanced Approach. A Maturity Model28,29 is a framework for a progressive journey from a common practice starting point and advancing through several steps of continuous improvement to increase performance.

Table 1: Example of a Maturity Model for an MRV System

Increasing Maturity Levels of MRV System |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Common Practice |

Best Practice |

Digital MRV |

|

| Technologies | Uses common digital tools, e.g., spreadsheets. GHG reporting is mostly manual (>90%), | Uses more digital tools, e.g., information management system, databases, online platforms, software models but still lots of information not digitally automated (<50%). | Uses digital tools from end-to-end of the data trail for the key priority GHG sources and sinks, e.g., digital sensors and meters, remote sensing for data collection, smart contracts for automation of MRV Process, big data analytics, blockchain and distributed ledgers (DLT), artificial intelligence, etc. |

| Level of Timeliness | Reporting frequency between 1 to 5 years to a primary MRV Stakeholder (e.g., UNFCCC). Not real time. | More frequent reporting (draft and final reports at least annually). Different MRV Stakeholders and requirements, therefore different reporting needs and required a lot of time to prepare all required documentation to support various reporting needs. Not real time. | Real time, high resolution data acquisition, smart contracts enable close to real-time reporting to a variety of MRV Stakeholders. |

| Level of Transparency | Information about data sources (i.e., “metadata”) not complete. Data may be collected at variable intervals and frequency, but data access provided annually (not monthly or daily). Data trail has disconnects from step to step. | Metadata provided. Higher frequency of data collection (e.g., monthly), but typically still lots of effort to understand data trails. | High resolution of data spatially and temporally, e.g., second-by-second data points at a specific activities/operations in an organization, facility or project. High levels of metadata and organized supporting information (e.g., calibration reports) |

| Level of expert involvement | > 90% manual to do the MRV Process; generally uses IPCC lower Tier methodology with limited expertise. Difficult to get high quality data and specialists to do advanced MRV work. | > 50% manual to do the MRV Process, although supported with more digital tools; generally uses IPCC higher Tier methodology with more advanced specialists to do the MRV Process. | < 20% manual; most of the MRV Process is automatically done by computers, except for isolated cases requiring specialists to do parts of the MRV Process. Experts focus on supervising the MRV Process. |

| Quality and Integrity | Low data resolution and transparency, lack of commonality between MRV Programs and jurisdictions limits value of MRV Outputs. | Limited data resolution and transparency but with improved verifiability, lack of commonality between MRV Programs and jurisdictions limits the value of MRV Outputs. | High resolution of data and verifiability, enables consistent and detailed MRV Outputs between MRV Programs and MRV Stakeholders. |

| Budget and Cost | Low budget. MRV Process costs associated with manual non-automated data collection, calculations, reporting, review. Limited verification and certification happening due to high costs. | More budget available for fully resourced MRV System with a full-time MRV team, and for external specialists. | Higher capital cost to implement advanced digital tools, but lowest operating cost due to digital automation of the MRV Process. |

However, it is important to recognize there is not a binary distinction between the Basic Approach and the Advanced Approach. Hence, this guidance document is flexible according to the expectations and local context, and a user can develop a “hybrid approach”. For example, using the Advanced Approach for a key sector or industry (e.g., the cement sector) where this is strategically important, while using the Basic Approach for other sectors. Therefore, this section briefly describes the Advanced Approach for setting a detailed assessment, so users start to consider potential future options to enhance their MRV System.

The Basic Approach is intended to be faster, cheaper and require fewer resources to develop an initial MRV Strategy. This can be considered a “first pass”, “quick start” or “80-20 rule” approach. The Basic approach aims to achieve a reasonably high level of incremental benefits while using relatively few resources.

The Advanced Approach is intended to be used when the situation involves certain conditions, for example:

- An MRV System is already functioning and can be considered effective in meeting minimum requirements

- A basic MRV Strategy is already developed, and implementation is in progress

- Sufficient resources are available or accessible to develop and implement an advanced MRV Strategy, including building an advanced MRV System

- High-level support/ambition exists from appropriate leaders that want to have an advanced MRV System, ideally as part of an integrated change management process30

A good example and explanation of the different approaches and relative effort from a Basic Approach to an Advanced Approach is provided by the Principles for Digital Development31.

Step 3 – Identify MRV Stakeholders Needs and Goals

MRV Stakeholders’ needs generally arise from Climate Governance (e.g., international agreements), MRV Governance and Frameworks (e.g., MRV Standards), as well as Climate Programs (e.g., regulations and markets). Different types of MRV Stakeholders each have varying needs and goals, though they can be directly related. For example, a company is required by government laws or Climate Programs to submit a report on its GHG emissions (an “MRV Output”). The government needs the MRV information (e.g., GHG emissions report) to make decisions on how to design and operate Climate Programs to manage and mitigate GHG emissions. The company might also need to provide the same or a similar report to other MRV Stakeholders, such as its investors or its customers (e.g., for concessional finance, or if a supply chain or trade requirement exists).

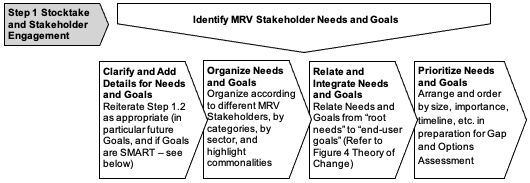

Figure 7: Identify, Clarify, Organize, Relate, Integrate, and Prioritize Needs and Goals

Although needs and goals are related, this guidance document differentiates between needs and goals (refer to Figure 1 and Figure 6):

Needs are current and fundamental minimum requirements, such as delivering a GHG emissions report as defined by the MRV Stakeholder (e.g., by a specific date and according to a specific MRV Standard).

Goals (sometimes called “end-goals”) are typically in the future, are more ambitious and go beyond what is required to satisfy current needs. For example, whereas a certain level of financial resources is needed to operate an MRV System to produce the GHG emissions report needed by the MRV Stakeholder, a goal would be to improve the MRV System so it can produce more information and data, that is more accurate and timely, to help attract and mobilize more climate finance to implement more climate actions.

Ideally, MRV Stakeholders define their goals with a structured process, so the goals (i.e., how the MRV Stakeholder defines success in their ambition to advance to the next level) are SMART:

-

Specific

- Define the activities, including the inputs, process, tasks, or outputs and outcomes to be achieved

- Assign responsibility to persons or organizations to do the activities and produce the outputs

-

Measurable

- Define a quantitative metric (e.g., data collected, reports completed, level of accuracy) for the activities and goal in order to track progress

-

Achievable

- Perform a “reality check” – whether or not sufficient resources (e.g., time, budget, experts) are available to do the activities et cetera to accomplish the goal

-

Relevant

- Consider the goals within the evolving context (e.g., national or sectoral, developments in Climate Governance and MRV Governance and Climate Programs, technology and economic trends related to MRV innovations) to check alignment, synergy and preparedness for future trends

- Consider the national circumstances such as national development goals and domestic climate targets and policies (such as Nationally Determined Contributions)

-

Time-bound

- Define the overall timeframe for the goals (e.g., immediate, short-term, long-term)

- Determine a “critical path” of start times and end times for activities and milestones for outputs

In practice, it is not common for MRV Stakeholders to have such clearly articulated goals. Typically, there is limited assessment of what is “Achievable”, and resources are scarce. It is also often difficult for MRV Stakeholders to consider “Relevant”, as they might not be aware of future trends or be unable to manage the associated uncertainty.

Where goals are not clear, additional stakeholder engagement (refer to Step 1.2) should include discussions to obtain information to help identify and clarify MRV Stakeholder needs and goals. This raises awareness of, and helps build support for, development of an MRV Strategy, to ensure MRV effectiveness to meet the more clearly articulated MRV Stakeholder goals.

Identifying MRV Stakeholders’ current and future needs and goals should consider the MRV Categories (e.g., finance, inventories, mitigation, NDC), and that there might be different MRV System maturity levels that exist and be needed for each MRV Category. These might vary from very basic MRV with no formal MRV System in place; a newly established MRV System; or a fully operational and optimized MRV System (refer to Table 1).

MRV Systems very often have differing maturity levels between sectors, reflecting the sectors’ differences in terms of size (e.g., GHG emissions, GDP) and priority (e.g., job creation, investment, government policies). These factors are part of identifying and defining MRV Stakeholder needs and goals.

Therefore, it is important to organize the different MRV Stakeholder needs and goals, relating these needs and goals from one MRV Stakeholder to another. It can be useful to start with the end-user (e.g., Climate Program or government body) and then identify the needs and goals through MRV Outputs, to the MRV System and MRV Process, and to the MRV Inputs. Refer to examples in Table 2.

As illustrated in Figure 7, identifying and assessing MRV Stakeholder needs and goals can be performed and organized in many combinations, for example by:

- type of MRV Stakeholder (e.g., Climate Programs, Climate Finance, MRV Program or MRV System manager, reporting entity)

- type of MRV Outputs (e.g., reports, data assessments, compliance assessments, capacity building)

- phase of an MRV System (e.g., design, build, operate)

- type of MRV Inputs (e.g., human resources, data, tools, budget, institutional arrangements)

- sectors (e.g., energy, industry, waste, AFOLU)

- categories (e.g., NDCs, finance, mitigation, inventories)

- timeframes (e.g., short-term, medium-term, long-term)

- priority (e.g., urgent, high, medium, low)

It is important to include additional detail about the identified needs and goals. For example, both public finance and private finance can address climate change in different ways. Public finance often supports activities that benefit the public in general, such as sector studies to obtain informed analysis of GHG emissions and mitigation opportunities, demonstration of innovative solutions, and capacity building. Public finance helps to mobilize private finance by removing uncertainties and mitigating risks in order to make climate actions more attractive and “bankable”. Thus, the needs and goals for public finance and for private finance are different, and likewise the MRV requirements will be different (i.e., different MRV Outcomes with different MRV Outputs – refer to Figure 4).

It is useful to include detail about the needs for the MRV Outputs, MRV System, MRV Process and MRV Inputs. For example, the public finance for innovative solutions (e.g., new waste management systems or new digital MRV software that can save future costs when scaled) will have a different MRV report than for the private finance of climate actions. For example, early-stage investment in waste management projects reduces short-term GHG emissions at one site, and also lowers the cost for subsequent sites and investments, so it is economically feasible for future projects to reduce long-term GHG emissions.

Furthermore, it is useful to continue to “drill-down” into additional details. For example, the level of needs for human resources (e.g., MRV Inputs) that will perform the activities in the MRV Process to deliver MRV Outputs (e.g., GHG emissions report) needed by the MRV Stakeholder. In this case, in addition to identifying budget and time needed, it is important to identify both the amount of time a person is needed to do the work, as well as the type and level of expertise (e.g., a data technician to analyze data, or a biology PhD to customize methodologies to local conditions). Table 2 presents examples of different MRV Stakeholders’ “end-use needs and goals” and relates corresponding these to the MRV System, MRV Outputs and MRV Inputs.

Table 2: Examples for different MRV Stakeholders relating their ultimate ‘end-user’ Needs and Goals to MRV Outputs and MRV Inputs

| Different MRV Stakeholders |

Needs and Goals

|

MRV System Needs to enable MRV Outputs to satisfy MRV Stakeholder | MRV Inputs Needs to enable MRV Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facility MRV Manager | Needs: Comply with government regulations and laws | Produce a GHG emissions report according to recognized MRV Standard, and to submit GHG emissions report to government MRV Program |

MRV consultant $25k budget 3 months |

| Goals: Reduce cost of compliance; implement modern MRV system; identify opportunities in the MRV system for cost reductions, financing options (e.g., subsidy to buy new equipment) | Install sensors within the facility at each operation (not just one sensor for entire facility) to generate high resolution data with high accuracy to inform decision making for MRV Resources |

More accurate sensors, data management systems and software IT consultant $75k budget 6 months |

|

|

Government Climate Program (an end-user) |

Needs: Track GHG emissions and emission reductions at the national, sectoral and entity levels; and obtain resources to manage and mitigate GHG emissions in accordance with NDC |

GHG emissions reports (from reporting entities) according to MRV Standard (requirements, report format) and delivered on time IT system to manage GHG emissions reports |

Personnel with MRV expertise on IPCC NGGI and ISO 14064, External MRV and IT consultants $500k Annual reporting cycle process management |

| Goals: Deploy more public and private finance to more of the most cost-effective climate actions to mitigate GHG emissions in priority sectors; and do that as responsibly-fast as possible (e.g. “Just Transition”) | Augment GHG emissions reports with detailed economic assessments and develop policy, programs and economic instruments to engage financial sector and companies (suppliers and buyers of low-carbon tech) |

Augment MRV processes with facility audits (e.g., energy audit), onsite economic assessments, sector technology roadmaps Several consultants $500k Multi-year assessments |

|

|

Climate Finance (e.g., bank, investor) (an end-user) |

Needs: Stable and transparent government regulations. Climate Programs and sufficient project performance data (actual, projected) to demonstrate financial and environmental returns, scalability and transformational potential and enable reliable business case decision-making necessary to unlock flows of climate finance | Multistakeholder buy-in and coordination on MRV Program and MRV System design and management based on standardized and interoperable data systems | Studies on current and future capabilities, costs and options for MRV System, MRV Process, MRV Inputs |

| Goals: Deploy capital to high priority transition and resilience projects with low risk and high success rates in terms of short-term and long-term financial, environmental and transformational metrics | Standardized and structured GHG emissions and economic information with very high confidence, high resolution, high frequency (sensors at specific equipment and operations, hourly or near real time) | Climate Finance Taxonomy with structured templates in electronic format and machine readable (e.g., XBRL) to enable robust data analytics for investment decisions and ongoing performance | |

|

Environmental NGO (e.g., ‘watchdog’) (an end-user) |

Needs: Access to transparent information to judge if MRV Outputs, MRV System, MRV Inputs are acceptable quality (e.g., environmental integrity) | Ability for users to easily download recent and historical GHG reports from MRV System online portal; compile research and database integrating multiple diverse resources to perform quality assessments |

Impartial technical experts $50k donations and sponsors Continuous assessments |

| Goals: Ability to influence companies to increase ambition in mitigation and climate actions | Ability to interact effectively and with coordination with the company, workers, consumers, supply chain regarding MRV capabilities and information | Stakeholder engagement, public relations, communications experts, contact lists and networks, resources (websites, blog posts, social media…) |

As described in Table 2 above, an MRV Output such as a GHG emissions report can have multiple MRV Stakeholders, and each MRV Stakeholder might have different uses:

Government MRV Program decides if the company as a reporting entity is fully complying with government regulations

Climate Finance investor decides if there is a good investment to mitigate GHG emissions at the company or if the company share price is properly valued

Environmental NGO decides if the GHG emissions reported are credible and if the company is behaving responsibly (i.e., “social licence to operate”) to the larger community (e.g., workers, consumers, suppliers, citizens…) and if the company can be more ambitious in helping achieve climate goals.

Similarly, it is important to assess the needs for the data and information in terms of criteria such as the MRV Standards and MRV Principles. There are many types of MRV Principles that can be useful to add detail to specific aspects of identifying and assessing MRV Stakeholder needs and goals. The Basic Approach should use the TRACC principles (Transparency, Relevance, Accuracy, Completeness, Consistency) as a framework to guide the assessment of needs and goals, and the subsequent Gap Assessment. The following table presents a simple example.

Table 3: Example to Organize Needs and Goals corresponding to performance for the MRV Principles

| Principles | Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Current | Needs | Goals | |

| Accuracy | Unknown values | Accuracy / uncertainty qualitatively assessed | Accuracy quantitatively assessed and improvements implemented to achieve > 80% and independently reviewed |

| Completeness | Not all sectors, sources and sinks included | All sectors, sources and sinks assessed and included where material | All sectors, and all sources greater than 0.1% included in inventory for each GHG. |

| Consistency | et cetera | et cetera | et cetera |

| Relevance | et cetera | et cetera | et cetera |

| Transparency | et cetera | et cetera | et cetera |

It will likely be necessary to calibrate MRV Stakeholder expectations against realistically achievable interventions. That is, to optimize the available budget to achieve the most effective MRV System. For example, MRV Stakeholders might initially seek 100% coverage of all facilities and greenhouse gases (i.e., principle of “completeness”). For some sectors, achieving 100% coverage results in excessive MRV System costs, but credible coverage, such as 80% of facilities and 95% of greenhouse gas emissions (in tCO2e) might be achieved at much more reasonable cost. To optimize resources, regulators (i.e., Climate Program managers) typically set minimum thresholds of participation, such as facilities emitting more than 25,000 tCO2e per year. This captures the vast majority of GHG emissions (e.g., more than 90%), but keeps the number of facilities participating manageable (such as less than 1000 for a medium sized country), reducing costs for the Climate Program and sector participants.

Conversely, MRV Stakeholders may request annual reporting, but monthly or quarterly reporting might be achievable at negligible extra cost, enabling better facility management and mandatory disclosures by public companies.

MRV Stakeholders might not be aware of resource limitations and trade-offs, and need the opportunity to consider how compromises can be made between different MRV Stakeholders’ objectives and priorities and resource and other constraints. Ideally, MRV practitioners will have the opportunity to engage MRV Stakeholders in the development and review of an MRV Strategy. Such transparent and inclusive engagement approaches are important to the development of stakeholder trust and credibility in the MRV System.

As described above, an important criterion associated with MRV Stakeholders’ needs and goals is the timeframe to achieve such needs and goals, as well as for the development and implementation of an MRV Strategy and MRV System to support such needs and goals. It is important to consider current and future needs, and reasonable low-carbon transition pathways. For example, it may not be necessary to have facility level data now, but if an emissions trading scheme is planned in the medium term, facility level data will be required in the future. It is therefore important to ensure that current MRV System design is able to evolve to accommodate future needs, rather than having to rebuild at a later date.

The user can develop a short-term MRV Strategy to achieve incremental improvements and/or a long-term MRV Strategy in recognition of the constantly evolving “state of the art” of MRV and MRV Stakeholder needs and goals (e.g., increasingly ambitious and transformational step change climate strategies). In such circumstances, it might be appropriate to create a bridging document of short term to long term MRV Strategies.

It is useful to organize and prioritize MRV Stakeholders’ needs and goals according to magnitude, for example:

- emissions or emissions reductions of the sector and category;